Aperture is one of the three pillars of photography (the other two being Shutter Speed and ISO), and certainly the most important. In this article, we go through everything you need to know about aperture and how it works.

Contents

- 1 What is Aperture?

- 2 Aperture Explained in Video

- 3 How Aperture Affects Exposure

- 4 How Aperture Affects Depth of Field

- 5 What Are F-Stop and F-Number?

- 6 Large vs Small Aperture

- 7 How to Pick the Right Aperture

- 8 Setting Aperture in Your Camera

- 9 Minimum and Maximum Aperture of Lenses

- 10 Examples of Aperture Use

- 11 Everything Aperture Does to Your Photos

- 12 Aperture FAQ

- 13 Summary

What is Aperture?

Aperture can be defined as the opening in a lens through which light passes to enter the camera. It is an easy concept to understand if you just think about how your eyes work. As you move between bright and dark environments, the iris in your eyes either expands or shrinks, controlling the size of your pupil.

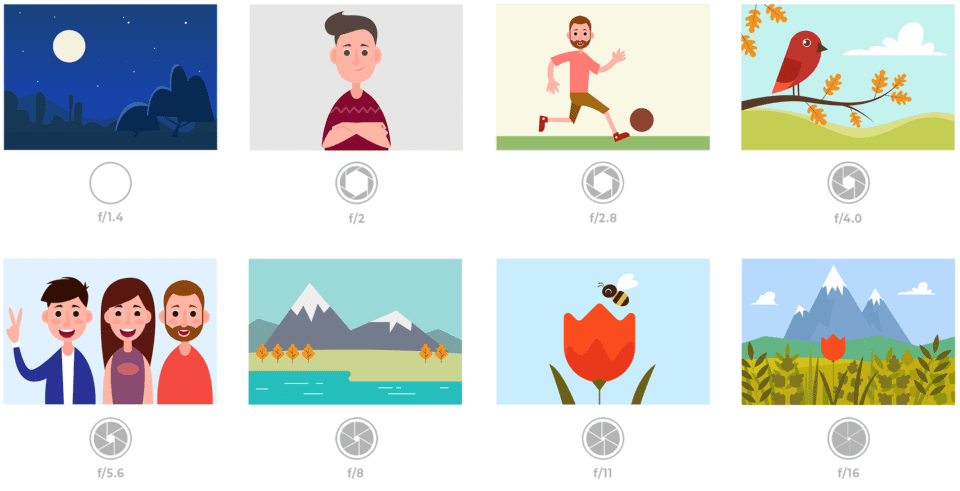

In photography, the “pupil” of your lens is called aperture. You can shrink or enlarge the size of the aperture to allow more or less light to reach your camera sensor. The image below shows an aperture in a lens:

Aperture can add dimension to your photos by controlling depth of field. At one extreme, aperture gives you a blurred background with a beautiful shallow focus effect.

At the other, it will give you sharp photos from the nearby foreground to the distant horizon. On top of that, it also alters the exposure of your images by making them brighter or darker.

Aperture Explained in Video

If you prefer to understand how aperture works visually, we put together a video for you that goes through most of the basics. In the video, we go through what aperture is, how it works and we also show how it affects things like depth of field and bokeh, which are covered further down in this article.

If you are ready to move on, the information presented below has a lot more in-depth material.

How Aperture Affects Exposure

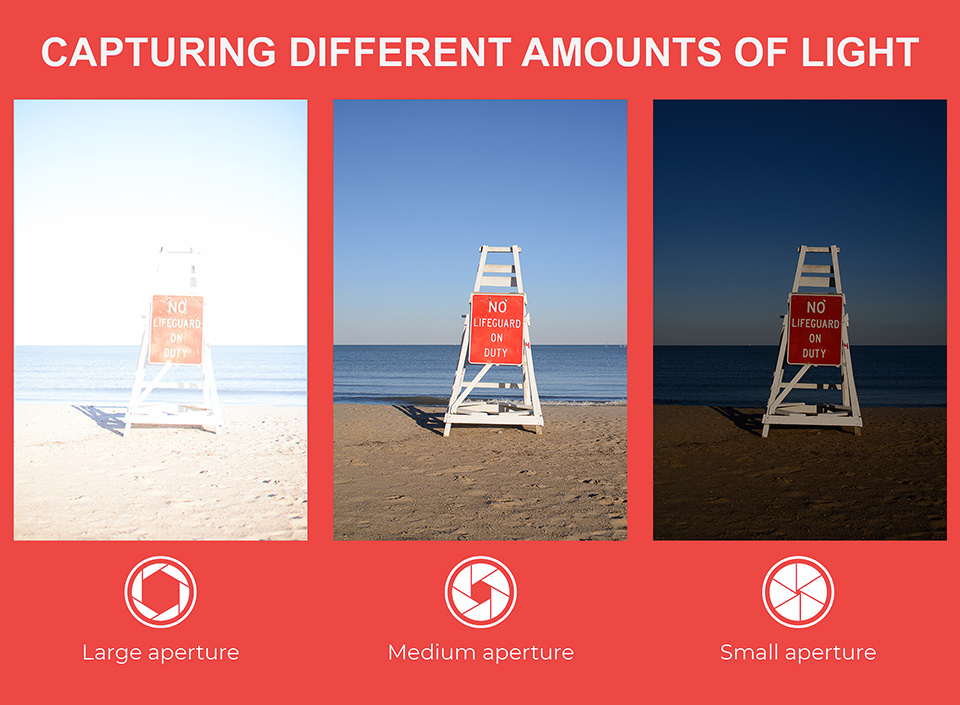

Aperture has several effects on your photographs. One of the most important is the brightness, or exposure, of your images. As aperture changes in size, it alters the overall amount of light that reaches your camera sensor – and therefore the brightness of your image.

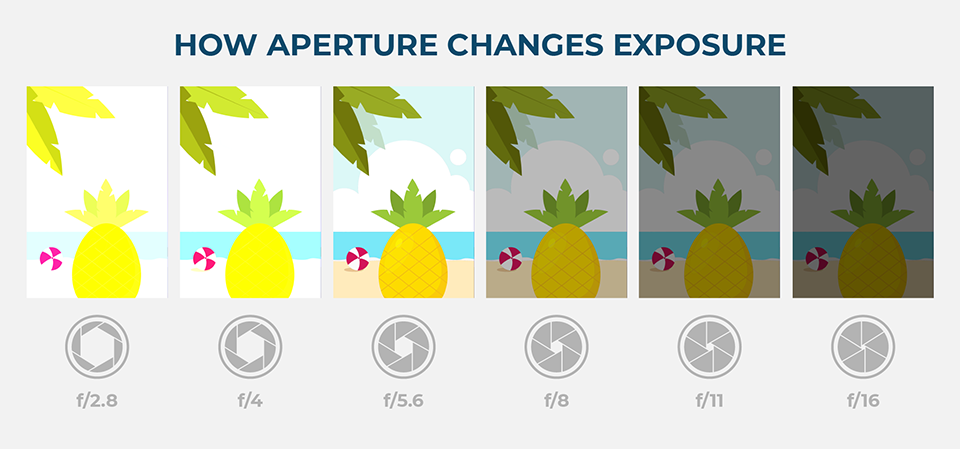

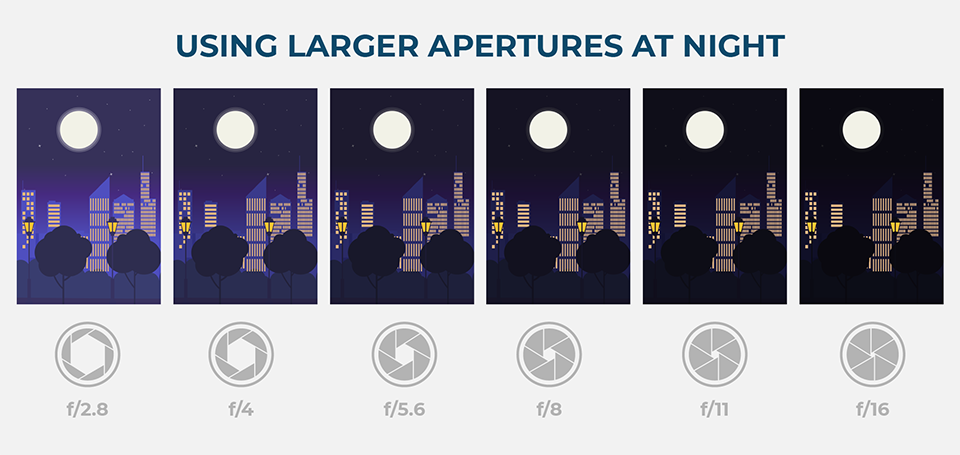

A large aperture (a wide opening) will pass a lot of light, resulting in a brighter photograph. A small aperture does just the opposite, making a photo darker. Take a look at the illustration below to see how it affects exposure:

In a dark environment – indoors, or at night – you will probably want to select a large aperture to capture as much light as possible. This is the same reason why your pupils dilate when it starts to get dark.

How Aperture Affects Depth of Field

The other critical effect of aperture is depth of field. Depth of field is the amount of your photograph that appears sharp from front to back. Some images have a “thin” or “shallow” depth of field, where the background is completely out of focus. Other images have a “large” or “deep” depth of field, where both the foreground and background are sharp.

In the image above, you can see that the girl is in focus and appears sharp, while the background is completely out of focus. The choice of aperture played a big role here. I specifically used a large aperture in order to create a shallow focus effect. This helped me bring the attention of the viewer to the subject, rather than busy background. If I had chosen a much smaller aperture, I would not have been able to separate my subject from the background as effectively.

One trick to remember this relationship: a large aperture results in a large amount of both foreground and background blur. This is often desirable for portraits, or general photos of objects where you want to isolate the subject. Sometimes you can frame your subject with foreground objects, which will also look blurred relative to the subject, as shown in the example below:

Quick Note: The way the foreground and the background out-of-focus highlights are rendered by the lens in the above example is often referred to as “bokeh“. Although bokeh is the property of a lens, one can yield shallow depth of field with most lenses when using a large aperture and close camera to subject distance.

On the other hand, a small aperture results in a small amount of background blur, which is typically ideal for some types of photography such as landscape and architecture. In the landscape photo below, I used a small aperture to ensure that both my foreground and background were as sharp as possible from front to back:

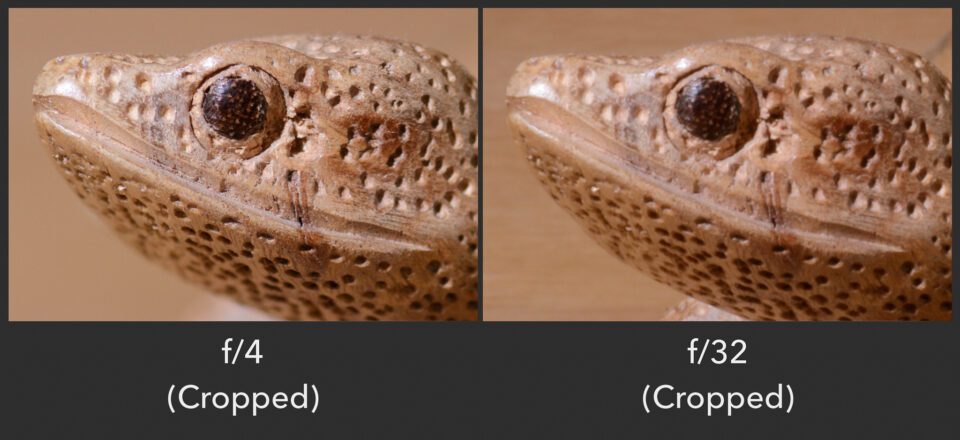

Here is a quick comparison that shows the difference between using a large vs a small aperture and what it does to the subject relative to the foreground and the background:

As you can see, the photograph on the left only has the head of the lizard appearing in focus and sharp, with both foreground and background transitioning into blur. Whereas the photo on the right has everything from front to back appearing sharp. This is what using large vs small aperture does to photographs.

What Are F-Stop and F-Number?

So far, we have only discussed aperture in general terms like large and small. However, it can also be expressed as a number known as “f-number” or “f-stop”, with the letter “f” appearing before the number, like f/8.

Most likely, you have noticed this on your camera before. On your LCD screen or viewfinder, your aperture will look something like this: f/2, f/3.5, f/8, and so on. Some cameras omit the slash and write f-stops like this: f2, f3.5, f8, and so on. For example, the Nikon camera below is set to an aperture of f/8:

So, f-stops are a way of describing the size of the aperture for a particular photo. If you want to find out more about this subject, we have a much more comprehensive article on f-stop that is worth checking out.

Large vs Small Aperture

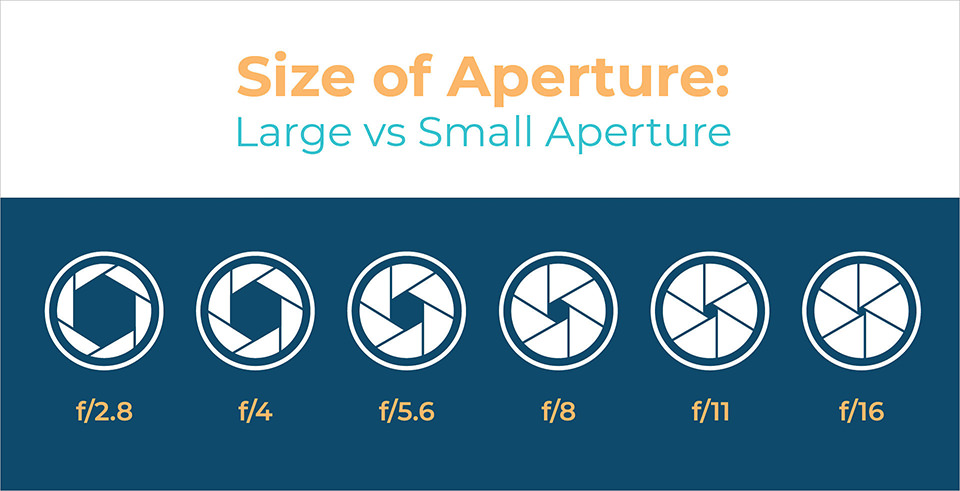

There’s a catch – one important part of aperture that confuses beginning photographers more than anything else. This is something you really need to pay attention to and get correct: Small numbers represent large, whereas large numbers represent small apertures.

That’s not a typo. For example, f/2.8 is larger than f/4 and much larger than f/11. Most people find this awkward, since we are used to having larger numbers represent larger values. Nevertheless, this is a basic fact of photography. Take a look at this chart:

This causes a huge amount of confusion among photographers, because it’s completely the reverse of what you would expect at first. However, as strange as it may sound, there is a reasonable and simple explanation that should make it much clearer to you: Aperture is a fraction.

When you are dealing with an f-stop of f/16, for example, you can think of it like the fraction 1/16th. Hopefully, you already know that a fraction like 1/16 is clearly much smaller than 1/4. For this exact reason, an aperture of f/16 is smaller than f/4. Looking at the front of your camera lens, this is what you’d see:

So, if photographers recommend a large aperture for a particular type of photography, they’re telling you to use something like f/1.4, f/2, or f/2.8. And if they suggest a small aperture for one of your photos, they’re recommending that you use something like f/8, f/11, or f/16.

How to Pick the Right Aperture

Now that you’re familiar with some specific examples of f-stops, how do you know what aperture to use for your photos? Let’s jump back to exposure and depth of field – the two most important effects of aperture. First, here is a quick diagram to demonstrate the brightness differences at a range of common aperture values:

Or, if you’re in a darker environment, you may want to use large apertures like f/2.8 to capture a photo of the proper brightness (once again, like when your eye’s pupil dilates to capture every last bit of light):

As for depth of field, recall that a large aperture value like f/2.8 will result in a large amount of background blur (ideal for shallow focus portraits), while values like f/8, f/11, or f/16 will help you capture sharp details in both the foreground and background (ideal for landscapes, architecture and macro photography).

Don’t fret if your photo is too bright or dark at your chosen aperture setting. Most of the time, you will be able to adjust your shutter speed to compensate – or raise your ISO if you’ve hit your sharp shutter speed limit.

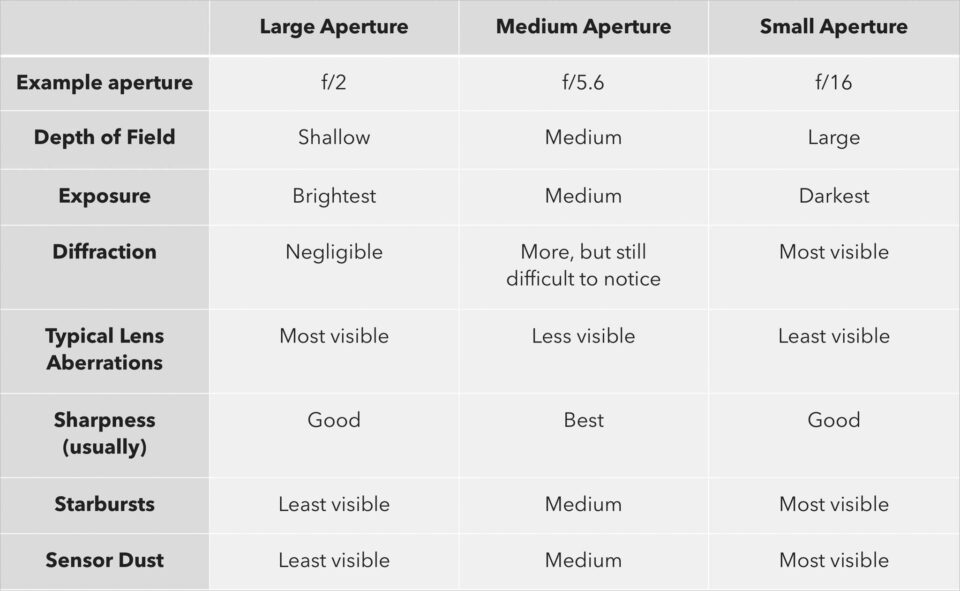

Here is a quick chart that lays out everything we’ve covered so far:

| Aperture Size | Exposure | Depth of Field | |

|---|---|---|---|

| f/1.4 | Very large | Lets in a lot of light | Very thin |

| f/2.0 | Large | Half as much light as f/1.4 | Thin |

| f/2.8 | Large | Half as much light as f/2 | Thin |

| f/4.0 | Moderate | Half as much light as f/2.8 | Moderately thin |

| f/5.6 | Moderate | Half as much light as f/4 | Moderate |

| f/8.0 | Moderate | Half as much light as f/5.6 | Moderately large |

| f/11.0 | Small | Half as much light as f/8 | Large |

| f/16.0 | Small | Half as much light as f/11 | Large |

| f/22.0 | Very small | Half as much light as f/16 | Very large |

Setting Aperture in Your Camera

If you want to select your aperture manually in your camera for a photo (which is something we highly recommend), there are two modes which work: aperture-priority mode and manual mode. Aperture-priority mode is written as “A” or “Av” on most cameras, while manual is written as “M.” Usually, you can find these on the top dial of your camera (read more also in our article on camera modes):

In aperture-priority mode, you select the desired aperture, and the camera automatically selects your shutter speed. In manual mode, you select both aperture and shutter speed manually.

Minimum and Maximum Aperture of Lenses

Every lens has a limit on how large or how small the aperture can get. If you take a look at the specifications of your lens, it should say what the maximum and minimum apertures are. For almost everyone, the maximum aperture will be more important, because it tells you how much light the lens can gather at its maximum (basically, how dark of an environment you can take photos).

A lens that has a maximum aperture of f/1.4 or f/1.8 is considered to be a “fast” lens, because it can pass through more light than, for example, a lens with a “slow” maximum aperture of f/4.0. That’s why lenses with large apertures usually cost more.

In contrast, the minimum aperture is not that important, because almost all modern lenses can provide at least f/16 at the minimum. You will rarely need anything smaller than that for day-to-day photography.

With some zoom lenses, the maximum aperture will change as you zoom in and out. For example, with the Nikon 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 AF-P lens, the largest aperture shifts gradually from f/3.5 at the wide end to just f/5.6 at the longer focal lengths. More expensive zooms tend to maintain a constant maximum aperture throughout their zoom range, like the Nikon 24-70mm f/2.8. Prime lenses also tend to have larger maximum apertures than zoom lenses, which is one of their major benefits.

The maximum aperture of a lens is so important that it’s included in the name of the lens itself. Sometimes, it will be written with a colon rather than a slash, but it means the same thing (like the Nikon 50mm 1:1.4G below).

Examples of Aperture Use

Now that we have gone through a thorough explanation of how aperture works and how it affects your images, let’s take a look at examples at different f-stops.

- f/0.95 – f/1.4 – such “fast” maximum apertures are only available on premium prime lenses, allowing them to gather as much light as possible. This makes them ideal for any kind of low-light photography when photographing indoors (such as photographing the night sky, wedding receptions, portraits in dimly-lit rooms, corporate events, etc). With such wide f-stops, you will get very shallow depth of field at close distances, where the subject will appear separated from the background.

- f/1.8 – f/2.0 – some enthusiast-grade prime lenses are limited to f/1.8 and offer slightly inferior low-light capabilities. Still, if your purpose is to yield aesthetically-pleasing images, these lenses be of tremendous value. Shooting between f/1.8 and f/2 typically gets adequate depth of field for subjects at close distances while still yielding pleasant bokeh.

- f/2.8 – f/4 – most enthusiast and professional-grade zoom lenses are limited to f/2.8 to f/4 f-stop range. While they are not as capable as f/1.4 lenses in terms of light-gathering capabilities, they often provide image stabilization benefits that can make them versatile, even when shooting in low-light conditions. Stopping down to the f/2.8 – f/4 range often provides adequate depth of field for most subjects and yields superb sharpness. Such apertures are great for travel, sports, wildlife, as well as other types of photography.

- f/5.6 – f/8 – this is the ideal range for landscape and architecture photography. It could also be a good range for photographing large groups of people. Stopping down lenses to the f/5.6 range often provides the best overall sharpness for most lenses and f/8 is used if more depth of field is required.

- f/11 – f/16 – typically used for photographing landscape, architecture and macro photography where as much depth of field as possible is needed. Be careful when stopping down beyond f/8, as you will start losing sharpness due to the effect of lens diffraction.

- f/22 and Smaller – only shoot at such small f-stops if you know what you are doing. Sharpness suffers greatly at f/22 and smaller apertures, so you should avoid using them when possible. If you need to get more depth of field, it is best to move away from your subject or use a focus stacking technique instead.

You have made it this far, but are you willing to learn more about aperture? So far we have only touched the basics, but aperture does so much more to your photographs. Let’s take a closer look.

Everything Aperture Does to Your Photos

Ever wondered how else aperture affects your photographs aside from brightness and depth of field? In this part of the article, we will go through all other ways aperture impacts your images, from sharpness to sunstars, and tell you exactly why each matters.

Before diving into too many specifics, here’s a quick list of everything aperture affects in photography:

- The brightness / exposure of your photos

- Depth of field

- Sharpness loss due to diffraction

- Sharpness loss due to lens quality

- Starburst effects on bright lights

- Visibility of camera sensor dust specks

- The quality of background highlights (bokeh)

- Focus shift on some lenses

- Ability to focus in low light (under some conditions)

- Control amount of light from flash

We have already introduced the first two earlier in the article, but that’s still quite a lot to go through! Clearly, aperture matters in many different areas of photography. Below, we will go into all these factors and how they work in practice.

Portrait photographers love using wide apertures like f/1.4 or f/2 to get their subject isolated from the foreground and background. It allows them to keep the subject the center of interest for the viewer, while making distracting elements appear blurred. Such “dreamy” portraits are quite popular in portrait photography, and rightfully so.

However, not all images are desired to be this way. Landscape and architecture photographers, for example, prefer the other side of the aperture spectrum, using small apertures like f/8 and f/11. Their goal is to get both the foreground and the background elements in focus simultaneously.

The Negative Effect of Diffraction

So, if you’re a landscape photographer who wants everything as sharp as possible, you should use your lens’s smallest aperture, like f/22 or f/32, right?

No!

If we go back and take a close look at the photo of the lizard from the previous chapter where I used apertures of f/4 and f/32, you can clearly see some problems. Here is how the two images look like when zoomed in to 100% view:

Here, you’re seeing an effect called diffraction. Physics majors will know what I’m talking about, but diffraction is a foreign concept to most people. So, what is it?

Diffraction is actually quite simple. When you use a tiny aperture like f/32, you literally squeeze the light that passes through your lens. It ends up interfering with itself, growing blurrier, and resulting in photos that are noticeably less sharp.

When do you start to see diffraction? It depends upon a number of factors, including the size of your camera sensor and the size of your final print. Personally, on my Nikon full-frame camera, I see hints of diffraction at f/8, but it’s not enough to bother me. I actually use even smaller apertures like f/11 and f/16 all the time. However, I try to avoid f/22 or anything beyond it, since I lose too much detail at that point.

Diffraction isn’t a huge problem, but it exists. Don’t be afraid to take pictures at f/11 or f/16 just because you lose a little bit of sharpness. In many cases, the added depth of field is worth the tradeoff.

Side Note

If your camera has a smaller sensor, you’ll see diffraction sooner. On APS-C sensors (like on Nikon D3x00 series, Nikon D5x00 series, Fuji X-series, Sony A6x00 series, and many others), divide all these numbers by 1.5. On Micro Four-Thirds cameras (like those from Olympus and Panasonic), divide all these numbers by 2. In other words, I don’t recommend using f/11 with a micro four-thirds camera, since it’s equivalent to f/22 with a full-frame camera.

How Lens Aberrations Hurt Sharpness

Here’s a fun one. For some reason, everyone wants to take sharp photos! One of the ways to do so is to minimize the visibility of lens aberrations. So, what are lens aberrations? Quite simply, they are image quality problems with a photo, caused by your lens.

Although most problems in photography are because of user error — things like missed focus, poor exposure, or distracting composition — lens aberrations are entirely due to your equipment. They are fundamental, optical problems that you’ll notice with any lens if you look too closely, although some lenses are better than others. For example, consider the image below:

What’s going on here? In this crop, most of the lights look smeared rather than perfectly round. On top of that, the crop just isn’t very sharp. That’s lens aberration at work! The lights didn’t look this blurry in the real world. My lens added this problem.

Aberrations can appear in several different forms. For example, it’s likely that your lenses are blurrier at certain apertures, or in the corner of the image. That’s also due to lens aberrations.

This article would be way too long if I explained every possible aberration in detail: vignetting, spherical aberration, field curvature, coma, distortion, astigmatism, color fringing, and more. Instead, it’s more important to know why aberrations occur, including how your aperture setting can reduce them.

It starts with a simple fact: designing lenses is difficult. When the manufacturer fixes one problem, another tends to appear. It’s no surprise that modern lens designs are extremely complex.

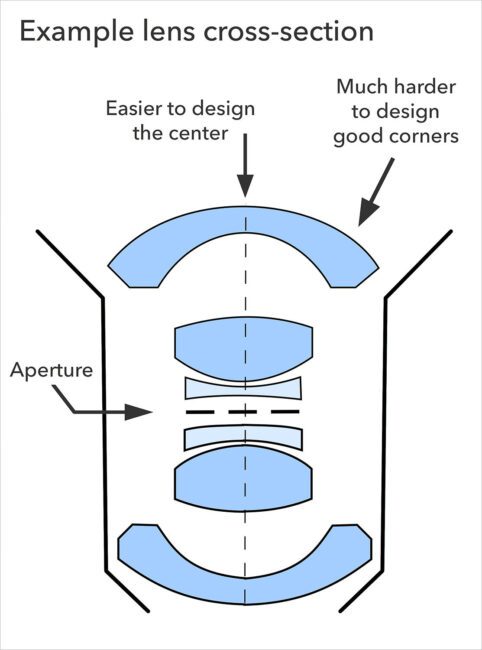

Unfortunately, even today’s lenses aren’t perfect. They tend to work fine in the center of an image, but everything gets worse near the edges. That’s because lenses are especially difficult to design around the corners.

Here’s a diagram that explains what I mean:

And that brings us to aperture.

Many people don’t realize a simple fact about aperture: it literally blocks the light transmitted by the edges of your lens. Note that this doesn’t lead to black corners in your photos, because the center regions of a lens can still transmit light to the edges of your camera sensor.

As your aperture closes, more and more light from the sides of your lens will be blocked, never making it to your camera sensor. Only the light from the center area will pass through and form your photo! As the diagram above shows, this central area is far easier for camera manufacturers to design. The end result is that your photos will have fewer aberrations at smaller and smaller apertures.

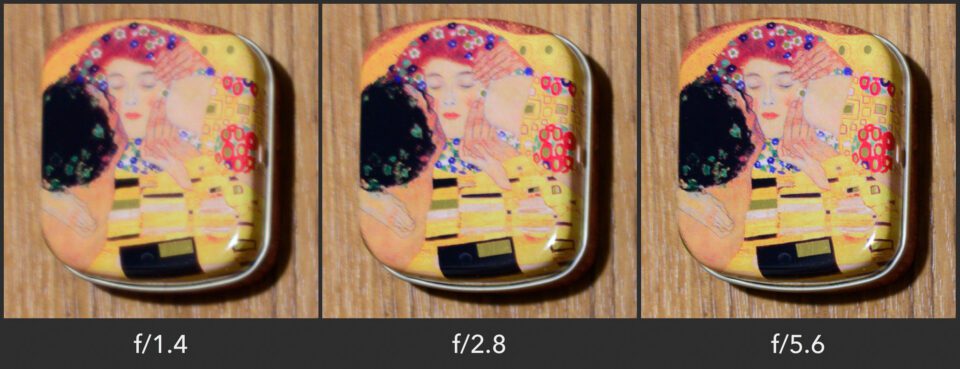

How does this look in practice? See the photos below (heavy crops from the top-left corner):

What you’re seeing above may look like an increase in sharpness, but it’s really a decrease in aberrations. The end result? At f/5.6, your photo – taken with an aperture that has less visible aberration – is much sharper than at f/1.4.

Here’s a key question, though: how does this balance out with diffraction, which harms sharpness in the opposite direction?

In practice, most lenses are sharpest around f/4, f/5.6, or f/8. Those apertures are small enough to block light from the edges of a lens, but they aren’t so small that diffraction is a significant problem. However, you’ll want to test this on your own equipment.

Of course, you can still take good photos at large apertures like f/1.4 or f/2. Portrait photographers sometimes pay thousands of dollars to get a lens exactly for that purpose! I’ve taken successful photos at everything from f/1.4 to f/22 — photos that wouldn’t be possible if I always used f/5.6.

Side Note

Some types of aberrations don’t change much as you stop down, or they may even get slightly worse. Axial chromatic aberration, for example – color fringes near the edges of your frame – often work that way. This is normal. It happens because a small aperture doesn’t inherently reduce aberrations; it simply blocks light that has passed through the edges of your lens. So, naturally, if the edges aren’t the source of your problem, you won’t see an improvement by stopping down.

Starburst and Sunstar Effects

Starbursts, also called sunstars, are beautiful elements that you’ll find in certain photographs. Despite the odd names – one, a type of candy; the other, a type of starfish – I always try to capture them in my landscape photos. Here’s an example:

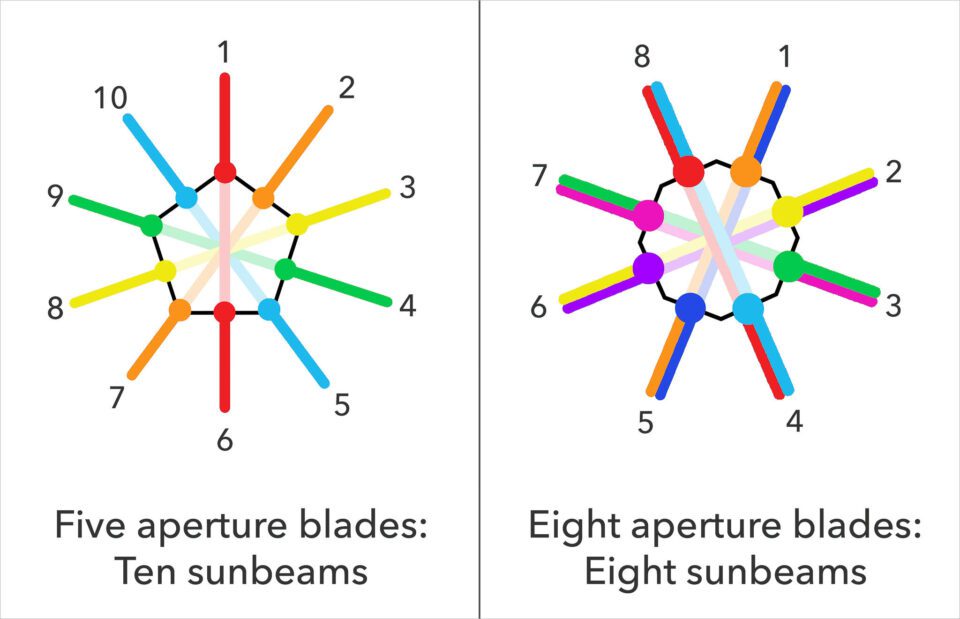

How does this work? Essentially, for every aperture blade in your lens, you’ll end up with a sunbeam. This only happens if you photograph a small, bright point of light, such as the sun when it is partly blocked. This is fairly common in landscape photography. If you want the strongest possible starburst, use a small aperture. When the sun is in my photo, I typically set f/16 purely to capture this effect.

Also, the starburst effect looks different from lens to lens. It all depends upon your aperture blades. If your lens has six aperture blades, you’ll get six sunbeams. If your lens has eight aperture blades, you’ll get eight sunbeams. And, if your lens has nine aperture blades, you’ll get eighteen sunbeams.

Wait, what?

That’s no typo. For lenses with an odd number of aperture blades, you’ll get twice as many sunbeams. Why is that?

It sounds strange, but the reason is actually quite simple. In lenses with an even number of aperture blades (and a fully symmetrical design), half of the sunbeams will overlap the other half. So, you don’t see all of them in your final photo.

Here’s a diagram to show what I mean:

Most Nikon lenses have seven or nine aperture blades, resulting in 14 and 18 sunbeams respectively. Most Canon lenses have eight aperture blades, resulting in eight sunbeams. I took the photo above using the Nikon 20mm f/1.8G lens, which has 7 aperture blades. That’s why the image has 14 sunbeams.

It’s not just the number of blades that matters, though — their shape is also important. Some aperture blades are rounded (which results in a more pleasant out-of-focus background blur), and others are straight. If your goal is to capture good starbursts, straight aperture blades typically produce more defined rays of light.

Again, some lenses are better than others in this regard. For the best results, find a lens that’s known to have good starbursts, and then set it to a small aperture like f/16. That’s going to give you the strongest definition in your starbursts.

NIKON D7000 + 24mm f/1.4 @ 24mm, ISO 100, 1/50, f/16.0

Finally, there’s one last related effect that I wanted to mention briefly. When you shoot into the sun, you might end up with flare in your photographs, as shown below. Depending upon your chosen aperture, the size and shape of this lens flare may change slightly. This isn’t a big deal, but it still exists.

Small Aperture and Unwanted Elements

When you shoot through things such as fences, dirty windows, plants, and even water droplets on your lens, you’ll probably be disappointed by photos taken with a small aperture.

Small apertures like f/11 and f/16 give you such a large depth of field that you may accidentally include elements that you don’t want to be in focus! For example, if you’re shooting at a waterfall or by the ocean, an aperture of f/16 could render a tiny water droplet on your lens into a distinct, ugly blob:

In cases like that, it’s better just to use a wider aperture, something like f/5.6, perhaps, in order to capture the water droplet so out-of-focus that it doesn’t even appear in your image. In this particular case, you could simply wipe the droplet off, but that’s not possible if you’re shooting through something like a dirty window.

Side Note

You might have realized that this section is really just an extension of depth of field, and that’s true! However, it’s a bit of a special case, so I decided to separate the two.

Another example of shooting through things is when a piece of dust lands on your camera sensor. Unfortunately, as you change lenses, this is very common. Dust specks on your camera sensor will show up very clearly at small apertures like f/16 or f/22, even if they’re invisible at something larger, like f/4.

Luckily, they are very easy to remove in post-production software like Photoshop or Lightroom, though it can be annoying if you have to remove dozens of them from a single photo. That’s why you should always keep your camera sensor clean. But, if it’s not clean, you should be wary of using small apertures.

If you happen to be taking pictures through other elements, keep this tip in mind as well – use a medium or wider aperture to make them less visible.

Changes to Your Bokeh

What is bokeh? It’s simply the quality of your background blur. If you take a lot of portraits or wildlife photos, you’ll end up with strongly out-of-focus backgrounds in most of your images. Naturally, you want them to look as good as possible! Different aperture settings will change the shape of your background blur. Why is that?

The background blur of your photographs always takes on the shape of your aperture blades. So, if your aperture blades are shaped like a heart, you’ll end up with heart-shaped background blur. Most of the time, that would qualify as distracting bokeh, although it’s kind of cute in this photo of two fake tortoises:

What makes this interesting is that, on some lenses, aperture blades change shape significantly as they open and close. Although not all lenses are this way, large aperture settings (such as f/1.8) often have rounder background blur than smaller aperture settings. You’ll also get more background blur at large apertures, since your depth of field is thinner.

Other lenses may be better at slightly smaller apertures, or they may have other, odd problems with background blur at wide apertures (such as choppy background blur in the corners). If bokeh is something that matters to you, you’ll want to test this on your particular lenses. Take some out-of-focus photos of a busy scene, each using a different aperture setting, and see which one looks the best. Most of the time, it will be the lens’s widest aperture, but not always.

Focus Shift Issues

With certain lenses – even if you’re in manual focus, and you don’t move your focus ring – your point of focus may shift as you use smaller and smaller apertures.

Obviously, this isn’t ideal. How do you tell if your lens has problematic focus shift? It’s pretty easy. Here are the steps:

- Put your camera on a tripod, and set your lens to manual focus.

- Find an object with small details that extends backwards, and focus at the center of it. A table typically works well, potentially with a tablecloth.

- Be sure: when you zoom in on a photo you take, you should see pixel-level details, as well as portions of the photo that are clearly out-of-focus.

- Take a photo at your lens’s widest aperture, and then at progressively smaller apertures. (You don’t need to take a photo every 1/3 stop; something like f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, and f/8 is good enough.) Be sure not to move your focus ring, and double check that you are using manual focus.

- On your computer, zoom into 100% on these photos and see if the sharpest point of focus moves continuously farther back as you stop down. The more it moves, the worse your focus shift issue is.

You’re done!

If your lens has extreme levels of focus shift, you’ll want to compensate for it:

- With your widest aperture, just focus like normal.

- With wide to medium apertures, around f/2.8 to f/5.6, enter live view (already using your intended aperture), then focus. Manual and autofocus both work fine.

- With small apertures like f/11 or f/16, your depth of field will be large enough to hide most focus shift problems, so just focus like normal.

Side Note

When it comes down to it, focus shift is just another type of lens aberration. The edges of your lens may not focus light the same as the center, so, by stopping down — again, blocking light from the edges — your focus point changes slightly. That’s the underlying reason for this effect.

Ease of Focusing

The autofocus system on your camera doesn’t work well unless it receives plenty of light.

Usually, this won’t be a problem. Even if you’re using a small aperture like f/16, your camera will still use a large aperture like f/2.8 to focus. It only stops down to f/16 once you actually take the photo.

However, that’s not always possible.

For example, if the largest possible aperture on your lens is pretty small, something like f/5.6 or f/6.3, your camera won’t be able to use a large aperture to help it focus. This is one reason why Nikon’s expensive 70-200mm f/2.8 zoom lens still focuses successfully in low light, while cheaper lenses (say, the 70-300mm f/4.5-5.6) start to miss focus more easily in the dark.

So, your lens’s maximum aperture matters for focusing more easily. Whether you’re shooting at f/2 or f/16, your camera focuses at the same aperture both times (aside from certain cameras in live view, or if you have an old lens with an all-manual aperture).

This effect might not matter to you if you’re a landscape photographer, but others may find it pretty important. At the very least, you’ll enjoy the brighter viewfinder (when using a DSLR) that comes from lenses with a large maximum aperture, and it’s never bad to have some extra low-light focusing capabilities.

Flash Exposure

When using speedlights or any kind of strobes, it is important to remember that aperture takes on a whole different role of controlling flash exposure. While shutter speed’s role becomes controlling ambient light, aperture’s function in flash photography is to purely regulate the amount of light the camera can record from a flash burst. This is a complex topic and we will write a separate article explaining this. We wanted to include it in this section, since flash is tightly correlated to lens aperture.

A Chart of Everything Aperture Does

When you learn the information above, you will know everything aperture does to your photos. However, that won’t happen instantly.

Understanding all the effects of aperture can take some time. Practice is your best friend. Go outside, take some photos, and get a feel for aperture yourself.

If it helps, I compiled the main information in this article into a chart:

Aperture FAQ

We put together some of the most frequently-asked questions related to aperture below.

Aperture can be defined as the opening in a lens through which light passes to enter the camera. It is expressed in f-numbers like f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8 and so on to express the size of the lens opening, which can be controlled through the lens or the camera. To read more about aperture with many examples and illustrations, click here.

Depth of field refers to the distance between the closest and the farthest objects in a photo that appears acceptably sharp. Generally, a large aperture results in a large amount of foreground and background blur, yielding shallow depth of field. On the other hand, a small aperture results in small amount of foreground and background blur, yielding wide depth of field.

Opening up lens aperture allows more light to pass into the camera, which allows the photographer to capture a properly exposed image at faster shutter speed. Stopping down, or reducing lens aperture, on the other hand, reduces the amount of light entering the camera, which requires use of slower shutter speed to yield an image with the same brightness.

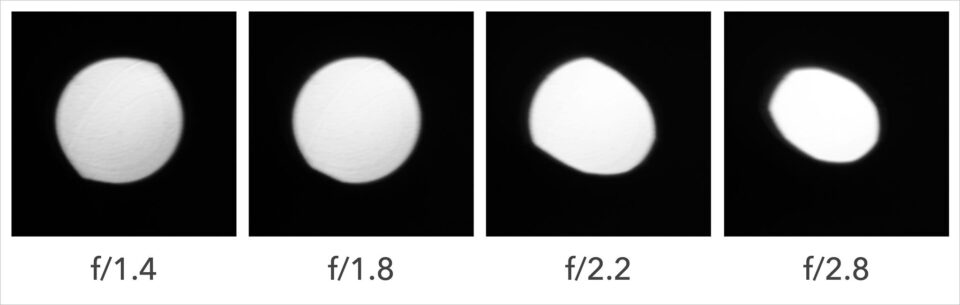

Bokeh refers to the quality of out-of-focus highlights of the image rendered by the camera lens. Using the maximum aperture of the lens will typically yield circular background highlights of large size, whereas stopping down the lens will typically result in highlights looking smaller and taking different shapes such as heptagon. These shapes depend on the number of aperture blades and their roundness. Here is an image of a 50mm f/1.4 prime lens stopped down to f/2.8 and f/4 apertures:

Maximum aperture is how wide a lens can be open. It is usually expressed in f-stops such as f/1.4 and stated on the name of the lens. For example, the Nikon 35mm f/1.4G lens has a maximum aperture of f/1.4, whereas the Nikon 50mm f/1.8G has a maximum aperture of f/1.8. Some lenses have variable maximum apertures that change depending on focal length. A lens like the Nikon 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 has a maximum aperture of f/3.5 at 18mm and f/5.6 at 55mm.

If your goal is to make an image with shallow depth of field, where the subject appears sharp while the foreground and the background appear blurry, then you should use very wide apertures like f/1.8 or f/2.8 (for example, if you are using a 50mm f/1.8 lens, you should set your lens aperture to f/1.8).

When photographing landscapes, you often want to have as much depth of field as possible in order to get both foreground and background looking as sharp as possible. In such cases, it is best to stop down your lens to small apertures like f/8 or f/11.

It really depends on what you are photographing and what you want your image to look like. Lower apertures like f/1.8 allow more light to pass through the lens and yield shallow depth of field. In comparison, higher aperture numbers like f/8 block light while yielding wider depth of field. Both have their uses in photography.

Changing lens aperture can affect focus due to focus shift. It is therefore best to stop the lens down to the desired aperture before focusing. On DSLR cameras, we recommend to use live view to focus at the desired aperture to reduce the negative effect of focus shift. This is due to the fact that DSLR cameras focus at the widest aperture.

That really depends on your camera’s sensor size, focal length of the lens and how close your camera is to your subject. Generally, a small aperture like f/8 will give you enough depth of field to be able to make most of your image sharp. However, if the subject is too close to your camera, you might need to either move back or stop down the lens even further to get everything looking sharp.

A large aperture yields shallower depth of field, which blurs everything in front and behind the focused subject, making parts of the photo appear blurry. Large apertures also show the weaknesses of the lens optical design, often resulting in visible lens aberrations. A small aperture, on the other hand, yields wider depth of field, making more of the image appear sharp. Small apertures also typically hide lens aberrations.

Most lenses are not designed to yield good sharpness at their maximum aperture, which is why it is often desirable to stop down to smaller apertures like f/5.6 to get the best results. However, the best aperture of the lens, or its “sweet spot” really depends on its optical design.

If you want to get your subject isolated from the scene and make the background appear blurry, you should open up the lens aperture to its maximum and get as close to the subject as possible. For example, if you are shooting with a 50mm f/1.8 prime lens, you should shoot at f/1.8 with your subject at a close distance. If you use a zoom lens, you should zoom in to the longest focal length and use the widest aperture, while being as close to your subject as you can. For example, if you are shooting with a 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 lens, you should zoom to 55mm, use the maximum aperture of f/5.6 and get close to your subject.

The maximum aperture of the lens, such as f/1.4.

The minimum aperture of the lens, such as f/22.

Summary

Aperture is clearly a crucial setting in photography and it is possibly the single most important setting of all. Aperture affects several different parts of your photo, but you’ll get the hang of everything fairly quickly. A small aperture makes your photos darker, increases depth of field, increases diffraction, decreases most lens aberrations, and increases the intensity of starbursts. A large aperture does the opposite.

Soon, this won’t be something that you even need to think about; you’ll remember it all naturally. Personally, if I want a starburst effect in my photos, I immediately know to use an aperture of f/16. When I need as much light as possible, I set a larger aperture like f/2.8 or f/2 without a second thought. It doesn’t take too much practice to get to that point.

Knowing how important aperture is, it shouldn’t be a surprise that, at Photography Life, we shoot in aperture-priority or manual mode most of the time. We practically never want the camera to select the aperture for us. It’s just too important, and it is one of those basic settings that every beginner or advanced photographer needs to know in order to take the best possible images.

As always, it’s best if you learn all this for yourself. Find something spectacular to capture, and put your new knowledge into practice. The more photos you take, the more you’ll learn. Aperture is no exception.

Below are some other related posts you might enjoy:

Hopefully, you found that this article explains the basics of aperture in a way that is understandable and straightforward.

If you are ready to move on, the next important camera setting to learn is f-stop, which we explain in Chapter 5 of our Photography Basics guide.